Kenneth landed in Scotland on the 7th of August 1942 with the rest of the 33rd FA Battalion. They moved south to Tidworth Barracks in England where they continued their training. They would be using the 105mm Howitzers in battle, but were also trained using the British 75mm Pack Howitzers. For a little over a month, the American soldiers trained during the day and enjoyed leisure time in the evenings. Soldiers enjoyed traveling into Glasgow or London when not on duty hours or spending time in pubs drinking and playing cards. However, the 15th of October saw the 33rd board the Monarch of Bermuda and the Langebby Castle in preparation for Operation Torch - the Allied invasion of North Africa.[1]

North Africa

Close to midnight on the 8th of November, 1942, the 33rd Field Artillery Battalion landed at Les Andalouses Beach near the city of Oran, Algeria. Battery “B” was the first battery ashore (Pvt. Bratt was in Battery "C") and using the smaller 75mm Pack Howitzers, was the first to return fire at 1100 hours.[2] Some believe Battery "B"'s engagement with the Vichy French right after landing to be the first artillery rounds fired by the US in the European Theater.[3] While Pvt. Bratt’s specialty was as a cook, he served as a loader during battle. He would move munitions around and load them into the guns during an engagement. On the 11th, an armistice went into effect, ending the fighting between the allies and the Vichy French. Years later, Kenneth would say, "Silly bastards thought they would fight with us after they surrendered."[4]

By January of 1944, the 33rd was on the move again moving east into Tunisia. They were assigned to provide support for the 26th Infantry in the Ousseltia Valley in Tunisia. The overall conflict lasted five days in which the 26th was able to take the valley. The 33rd passed through that engagement with little firing. Shortly after Ousseltia Valley, Battery “C” moved in to support the 91st Armored Field Artillery. Shortly after breaking away from the 33rd, two enemy planes attacked the battery destroying multiple vehicles and howitzers. Luckily, they were able to replace their equiptment within just a couple of days. By the middle of February the 33rd had fought its way 25 miles west of Sbielta, near a place called Kasserine Pass.[5]

The Kasserine Pass is a two mile wide gap in the Atlas mountains. The Allied army came up against the Nazi Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. The ensuing battle was the first large-scale meeting between American and German forces. It proved to be a difficult engagement for the Allies. It brought to the surface the inexperience of the troops as well as issues in command. The Allies were pushed back very quickly from their defensive positions by Rommel and his Panzer Divisions. The speed with which Rommel's Divisions came down on the Allied forces caused many soldiers to abandon their positions and run. By running, they lost most of their equipment to the advancing Germans. Pvt. Bratt was able to get a hold of a M1 garand. Due also to the speed with which the Allies retreated and the Germans advanced, Pvt. Bratt found himself behind German lines. During the night, Pvt. Bratt as well as other Allied soldiers made there way back across the front line to the Allied forces, two or three at a time.[6] At one point during the battle, one Howitzer section cut their time fuses to five tenths of a second. The Allies would lose the pass and Rommel would continue onward towards Tebessa and Thala before being pushed back on the outskirts of Thala. The casualties report from Kassarine would show the devastation that the Allies experienced. For every german soldier lost at the engagement, the Allies lost 5 (totaling to 10,000 casualties).[7]

Moving from Kasserine, the 33rd made its way to Gafsa and El Guettar by way of Bou Chebka and Morsott. The 1st Division moved quickly into place and caught the enemy unaware at Gafsa and then carried on to the east. Enemy resistance at El Guettar proved to be dogged. Luftwaffe flew over the area, strafing and dropping bombs. The 33rd suffered through the hot days and bitterly cold nights. Twenty-two days of combat ended on April 7th. A month later, the Germans had finally been kicked out of North Africa.[8]

Sicily

The 33rd took part in Operation Husky - the Invasion of Sicily. On July 10th, the 33rd landed on the beaches of Gela Sicily. It was a difficult landing and the gun positions were just five hundred yards from the water’s edge. A desperate counterattack was launched by the 11th Panzer Division on the 11th of July. An estimated 32 tanks progressed southward towards the Allied landing spot. All three batteries engaged in direct fire with the Germans. At one point, the Germans were so close that the 33rd lowered the barrels of the Howitzers until they were level with the ground and cut the time fuses on the ammunitions to air burst.[9] It took five hours to repel the Panzer Division resulting in the destruction of eight German tanks with others damaged.[10]

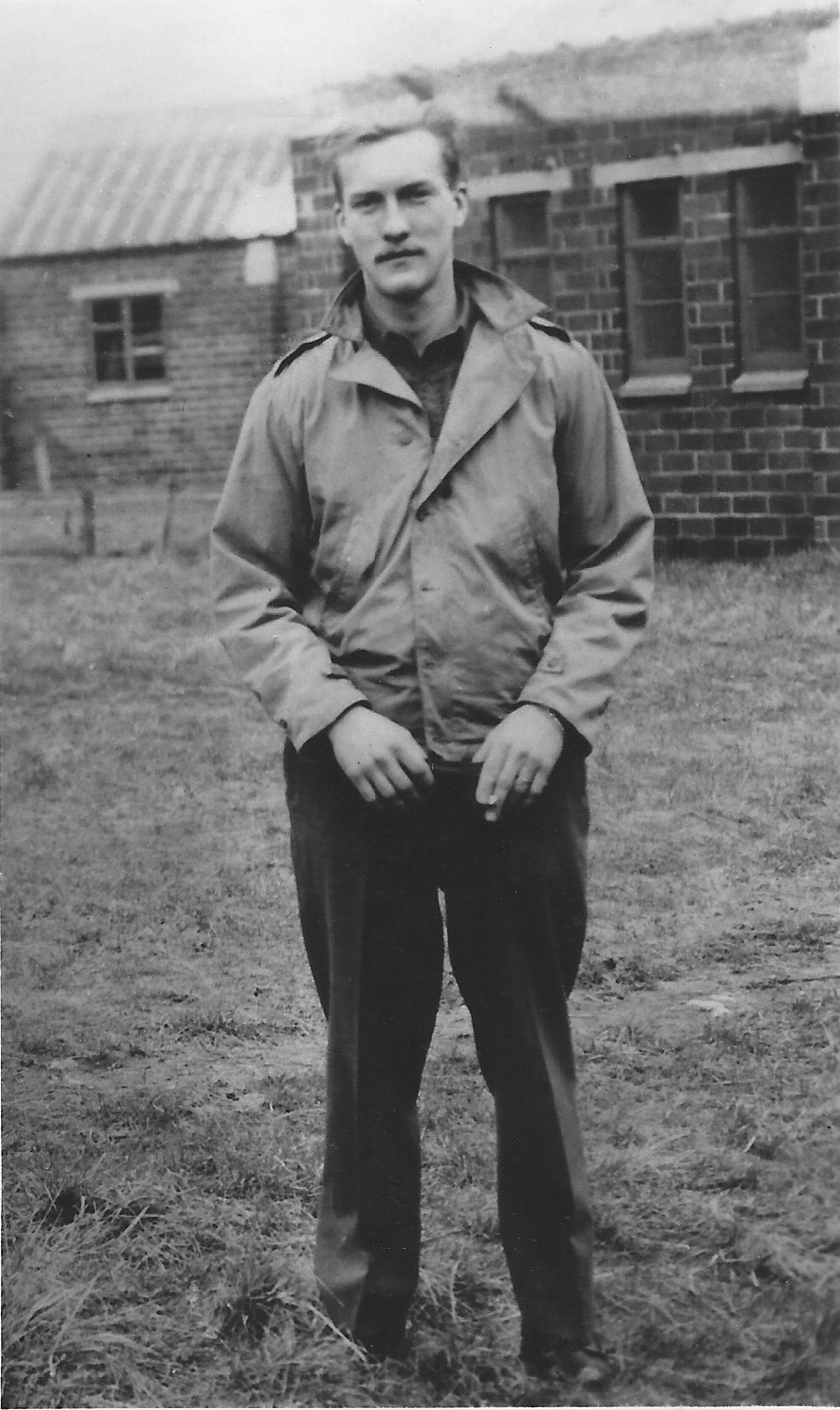

North Africa, 1942.

In tandem with Operation Husky was the dropping of hundreds of American paratroopers. They loaded in C-47 aircraft and took off from Tunisia. However, the American ground troops were alerted that there was going to be a German paratrooper drop. As the paratroopers floated towards the ground, the ground forces would pick them off. As Pvt. Bratt sighted one of the supposed enemy paratroopers, the man twisted in his harness and Pvt. Bratt saw the American patch on his uniform. He made his way over to help the paratrooper, who turned out to be a major, and they both took off into the woods. Coming upon a barn they holed themselves up in it only to find it full of a large supply of locally made wine. For three days Pvt. Bratt and the major remained drunk before venturing off to find their respective units.[11]

After the intensity of the landing at Gela, the roads into Sicily proved to be somewhat easier. While still meeting resistance along the way, they were able to move forward. Towards the center of the island of Sicily is the hill top town of Troina. It was a difficult engagement to take the hill. The 33rd provided support to the 26th Infantry as they repeatedly tried to take the town by providing constant fire. The 33rd is said to have caused the heaviest casualties and damage to the German troops in the entire Sicilian campaign.[12]

Troina turned out to be the end of the Sicilian campaign for the 33rd. They were moved to the vicinity of Palma De Montechiarro on the southern coast of Sicily. Here they were guarding roads and bridges and undertaking various duties.[13] On August 27th 1943, General George S. Patton made an address to the Division. This address was given in the wake of an incident in which he slapped two different soldiers who were suffering from battle fatigue earlier that month. As he stood there to apologize, the soldiers booed him. To begin the speech, Patton stood still for a brief moment and then said “I thought I'd stand here a while and let you see if I'm as big a son of a bitch as you think I am.” Recalling years later, Kenneth said that Patton had a high squeaky voice…and that he was that big of a son of a bitch.[14]

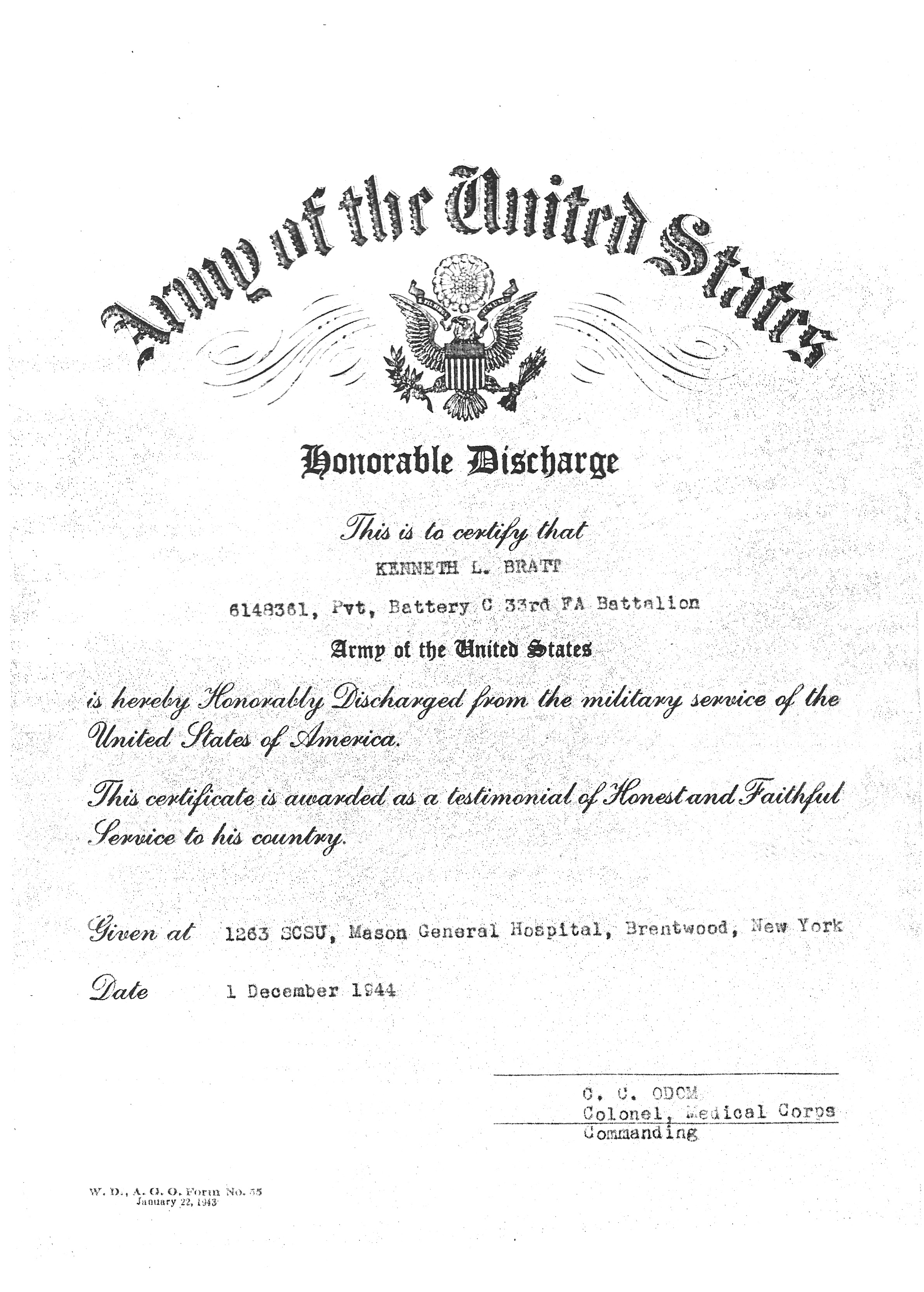

1 December, 1944.

The 33rd remained in Sicily until the end of October when they were able to board ships and return to England. They landed in Liverpool on the 6th of November, 1943, and moved up to Camp Piddlehinton in Dorchester the next day. It was here that the 33rd remained until D-Day the following year. However, Pvt. Bratt would not be joining the 1st Infantry in the Normandy invasion. By April of 1944, Pvt. Bratt was diagnosed with psychoneurosis, mixed type, chronic severe. He spent over a year in hospitals, eventually being shipped back to receive care in the United States. He first was in Jacksonville, Florida and finally moved up to Mason General Hospital in Brentwood, New York. On December 1st, 1944, after spending 5 years in the military, Private Kenneth Linnell Bratt was honorably discharged from the Army.[15]

Notes

1. U.S. Department of the Army, A Brief History of the 33d Field Artillery Battalion First Infantry Division, Washington: Department of the Army. 7. ↩

2. Barnes, Verdi B. Report of Action to the Adjutant General, Washington D.C. received HQS November 19, 1942. ↩

3. U.S. Department of the Army, A Brief History, 8. ↩

4. Rick Bratt, discussion with the author, April 2015. ↩

5. Barnes, Verdi B. Report of Action, Faid Pass, Tunisia, to Commanding General, 1st Infantry Division, March 1, 1943. ↩

6. Rick Bratt, discussion with the author, April 2015. ↩

7. Wikipedia contributors, "Battle of Kassarine Pass," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Kasserine_Pass (accessed May 3, 2015). ↩

8. U.S. Department of the Army, A Brief History, 11. ↩

9. Rick Bratt, discussion with the author, April 2015. ↩

10. U.S. Department of the Army, A Brief History, 12-13. ↩

11. Kenneth Bratt Jr., email to author, May 4, 2015. ↩

12. U.S. Department of the Army, A Brief History, 13. ↩

13. Bryde, Walter. Report of Action, August 9 to August 31, 1943, to Adjutant General, Washington, D.C., Septemeber 3, 1943. ↩

14. Rick Bratt, email to author, May 3, 2015. ↩

15. Report of Separation, Kenneth Bratt, separated in Brentwood, New York, December 1, 1944. National Archives, Washington, D.C. ↩